ENCOUNTERING DATA GAPS

For a product to be successful, it’s critical for designers to understand the environment in which the product will be used. For a medical device, this environment is often inside the human body. While some anthropometric data such as height, weight, and arm reach, are well documented, there are many critical anatomical measures that remain unknown, particularly in the realm of women’s health.

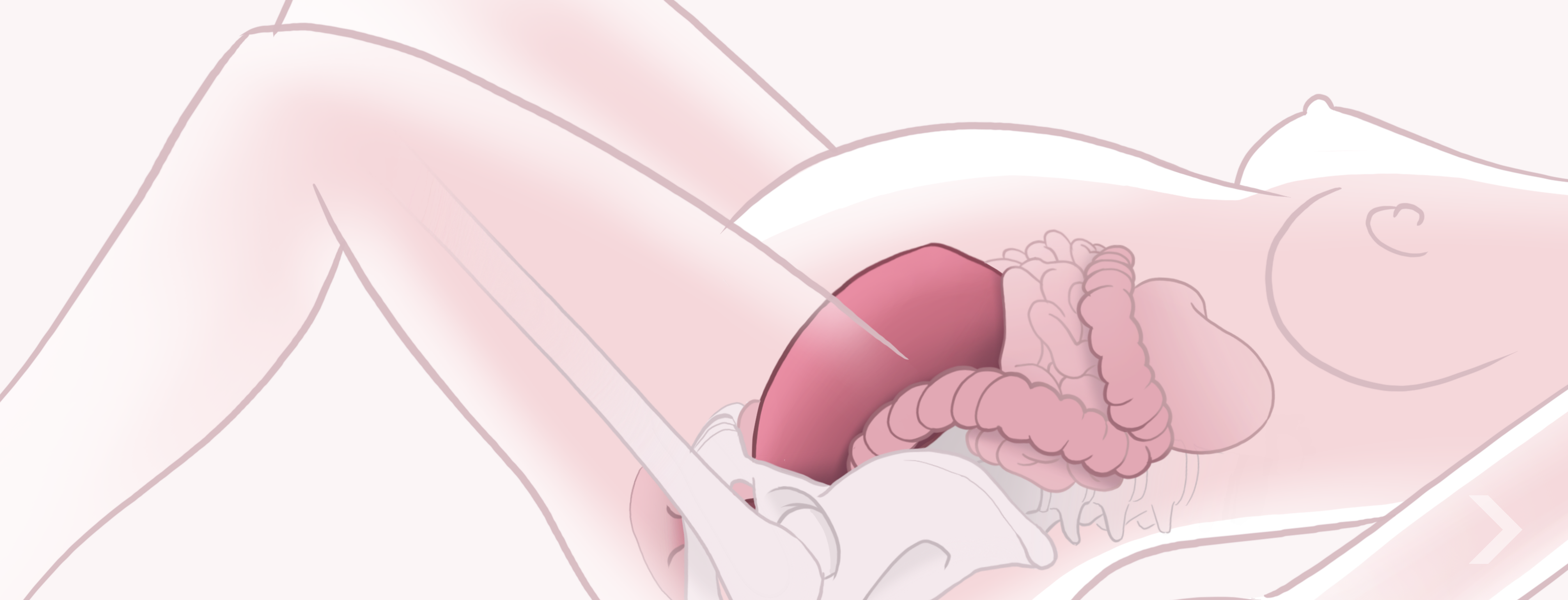

While collaborating with a medical partner to address postpartum hemorrhage (PPH,) the leading cause of maternal death worldwide, Kaleidoscope encountered this common product design challenge. During preliminary research, the team found that there was little to no readily available data on vaginal dimensions immediately following childbirth. The scarcity of this particular data is not surprising, as the anatomy changes rapidly postpartum. Understandably, collecting this data isn’t a priority for mothers or caregivers, who are focused on the wellbeing of the newborn. Nevertheless, this lack of data created a significant challenge for the Kaleidoscope PPH design team.

TOOLS FOR BRIDGING THE GAP

Whether we are creating a medical device, a smart pet collar, or an industrial freezer, the team at Kaleidoscope utilizes a number of different methods when designing for the unknown. One way we obtain the data we need is simply to collect it ourselves! Armed with calipers and tape measures, we might venture into the field or bring samples into our studio to take direct measurements. Direct observation, whether in person or through videos and photos, is another way we round out our understanding of a unique user experience.

Sometimes—like trying to determine dimensions of internal anatomy—this just isn’t feasible. In those cases, we turn to subject matter experts. Surgeons, with their deep experiential knowledge of anatomy, are able to describe what they have encountered in situ, providing additional insights into the nuanced aspects of human anatomy, such as texture, firmness and what it feels like to manipulate different anatomical structures. These insights proved to be a vital element in overcoming the data gaps encountered by the PPH design team.

OUT-OF-THE-BOX INSPIRATION

When the Kaleidoscope team explores new product categories, we find that drawing inspiration from successful analogous products is another valuable strategy. If we’re creating a handheld device, referencing power tools, hair dryers, or hot glue guns as adjacent products can help guide the design in the correct direction. The key here is relevance—referencing products familiar to end-users ensures that the design resonates with their expectations. If we are developing a surgical device for ophthalmologists, (who are used to small, delicate instruments that they control with their fingertips,) it would be more appropriate to reference delicate tools such as those used by sculptors than it would be to reference tools used by auto mechanics.

While designing for a post-partum hemorrhage solution, analogous products included menstrual cups and discs, which share similar placement within the vaginal canal. These adjacent products provided the Kaleidoscope team with a good starting point for shape and dimensions of the device, as well as inspiration for materials and durometers to explore. These analogous references were part of the constellation of information used by the PPH team while exploring potential solutions to our data gap.

EMBRACING FLEXIBLE SOLUTIONS

At the end of the day, secondary research can only get us so far. In the absence of precise anatomical dimensions, adaptability can be a powerful tool in the designer’s toolbox. Whether the solution is fully adjustable (like an office chair) or offers different size options (like audio earbuds with multiple size tips,) a thoughtfully designed adjustable or flexible product ensures that one size does NOT need to fit all—rather, we can design a solution that easily adapts to meet the needs of all users.

Being on the cutting edge of new product development often means navigating uncharted territory. At Kaleidoscope, we've mastered the art of designing for the unknown with a combination of creative data collection, analogous product inspiration, and thoughtful adaptability. By transforming uncertainty into opportunity for our partners, we create products and experiences that improve outcomes for everyone.

Back to Insights + News