Everyone has used an adhesive bandage, but which one is your favorite? Have you ever stopped to think about why? Bandage usability has real implications for patient care, safety, and user satisfaction. In this article, we examine how packaging, adhesive, and design choices impact the experience for end users.

Although adhesive bandages are typically classified as Class I medical devices by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), that doesn't mean usability is unimportant. Think about the last time you used one: Were you in pain? In a rush? Maybe trying to open and apply it with one hand? These are the kinds of real-world conditions that highlight the importance of thoughtful design. To demonstrate that human factors can be applied to even the simplest of devices, we evaluated the usability of four different bandages that can be found in any local drugstore.

The Bandages

We chose four different adhesive bandages to compare. These bandages were chosen for their brand recognition and variability in shape, size, and material type.

- Band-Aid - Flexible Fabric Knuckle & Fingertip Bandages, H-shape

- Niceful - Silicone Foam Dressing Gentle Border, square shape

- Nexcare - Waterproof Clear Bandages, hexagon shape

- Welly - Adhesive Flexible Fabric Bravery Badges, oval shape

Each bandage was evaluated based on key features and usability considerations, including the texture and flexibility of the fabric, the ease of removing the liner and applying the bandage, and the clarity of the instructions, labeling, and overall packaging design.

Methods and Results

In June 2025, 2 Human Factors Engineers (HFEs) from Kaleidoscope Innovation, Rebecca Chompff and Taylor Morgan, performed a systematic evaluation of 4 bandages and 10 key bandage features essential for successful and satisfactory use.

The usability of each bandage was discussed on a feature-by-feature basis. Each feature was subjectively rated on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 = Not Applicable, 1 = Poor, 2 = Okay, 3 = Good, and 4 = Great.

The 10 key bandage features that were assessed included:

- package labeling,

- unboxing,

- wrapper,

- unwrapping,

- material,

- adhesive,

- application,

- a 72-hour leave-on test,

- and removal post leave-on test.

The table below displays the subjective ratings for each bandage and bandage feature assessed during this evaluation:

The adhesive bandage(s) rated the highest and lowest for each key feature are discussed below:

- Package Labeling refers to all text and visuals displayed on the bandage container and was evaluated for its usability. Nexcare earned the highest score (4) for its clear and informative labeling, featuring concise text, large graphics, well-organized layout, and user-friendly “Easy to Apply” instructions printed on the side of the box. In contrast, Niceful and Welly received the lowest score (1). Niceful was marked down for its lengthy paragraphs and the use of medical terminology, such as “absorb exudate quickly,” which could be important for healthcare professionals but may confuse lay users. Welly scored poorly due to minimal information and prioritization of kid-friendly colors over clarity. Most of the information was printed on a disposable paper wrapper around the tin container, which has to be removed, and likely discarded, before use.

Figure 1. Bandage Packages – Left to right: Band-Aid, Nexcare, Niceful, Welly

Figure 1. Bandage Packages – Left to right: Band-Aid, Nexcare, Niceful, Welly

- 4Unboxing refers to the process of opening the new container to access the bandages inside. Niceful received the highest score (4) for its adhesive safety seal, which includes a pull tab sticker that aids the user in opening the box. Welly earned the lowest score (1) due to the absence of clear instructions or indicators on how to open the tin or identify its top side. Opening the Welly lid also required significant force, causing some bandages to fall out.

- Wrapper refers to the sealed paper or plastic covering of each individual bandage. Band-Aid received the highest score (4) for its paper wrapper, which features a “peel here” label printed on a prominent red bar next to the pull tabs. In contrast, Niceful received the lowest score (1) due to its oversized plastic wrapper, which creates unnecessary waste and lacks clearly identifiable pull tabs.

Figure 2. Wrapped Bandages – Left to right: Band-Aid, Nexcare, Niceful, Welly

Figure 2. Wrapped Bandages – Left to right: Band-Aid, Nexcare, Niceful, Welly

- Unwrapping refers to the process of opening the sealed paper or plastic covering each bandage. Niceful and Welly received the highest score (4) for their user-friendly design, featuring large peel tabs and wrappers that separated easily. Nexcare received the lowest score (2) because its wrapper was somewhat difficult to pull apart and often tore irregularly during opening. No bandage received a score of 1 in this category.

Figure 3. Unwrapped Bandages – Left to right: Band-Aid, Nexcare, Niceful, Welly

Figure 3. Unwrapped Bandages – Left to right: Band-Aid, Nexcare, Niceful, Welly

- Material refers to the surface of the bandage opposite the adhesive liner. Band-Aid earned the highest score (4) for its smooth, soft, and comfortable texture, along with the ability to stretch and conform to the body. Niceful received the lowest score (2) due to its slick plastic texture, which felt soft but less pleasant to the touch. No bandage received a score of 1 in this category.

- Adhesive refers to the sticky side of the bandage that adheres to the skin and was assessed by fingertip touch. Niceful received the highest score (4) for its sticky adhesive, which continued across the absorbent pad, indicating that the bandage would stay securely in place for the duration of wear. Nexcare received the lowest score (1) due to its lack of stickiness, which raised concerns about its ability to remain adhered to the skin.

- Application refers to the process of placing a bandage onto the skin—in our case, along the forearm. Niceful and Welly received the highest scores (4) for smooth application and visible adherence to both hairy and non-hairy skin. Nexcare received the lowest score (1) because proper application required careful attention to the performance of the application steps, particularly involving peeling individual border pieces from the bandage. The Nexcare bandage also requires more pressure to seal properly and showed poor adhesion on hairy skin.

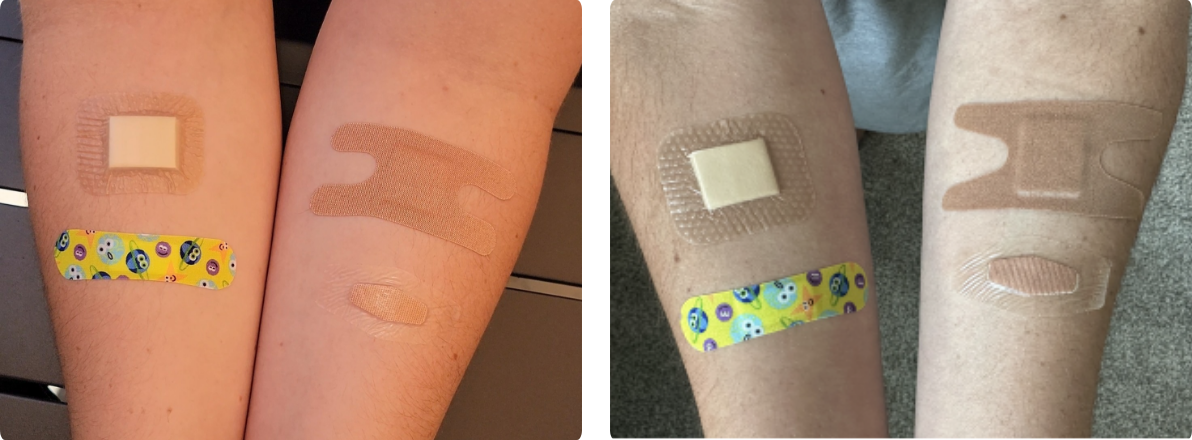

Figure 4 +5. All bandages immediately following application

Figure 4 +5. All bandages immediately following application

- Leave-On Test refers to a trial involving two researchers wearing each of the four bandages continuously on their forearms for 72 hours. During this period, both researchers took three showers, completed two workouts, and were exposed to average outdoor temperatures of 85°F. Nexcare and Welly received the highest score (4) for maintaining strong adhesion throughout the full 72 hours. Niceful received the lowest score (1) as it detached after just 6 hours for one researcher and 19 hours for the other—both shortly after their first shower. For one of the researchers, Band-Aid detached after their second shower, approximately 30 hours after application.

Figure 6. Niceful bandage (right), 19 hours after application and moments before it detached

Figure 6. Niceful bandage (right), 19 hours after application and moments before it detached

- Removal (post leave-on test) refers to the process of taking off the bandage after the 72-hour wear period described above. Notably, no bandage received a perfect score of 4 in this category. Welly received the highest score (3) for this removal, as it caused only minimal discomfort. Band-Aid received the lowest score (0) because one researcher experienced the bandage detaching after just 30 hours so it could not be fairly compared to the other bandages that adhered for the full 72-hours. Niceful also received the lowest score (0), as both researchers reported the bandage falling off prematurely—after 6 and 19 hours, respectively.

Final Thoughts

This evaluation has made clear that even though these bandages initially seem very similar, they each have specific strengths and weaknesses. The Band-Aid bandage wrapper has easily identifiable instructions for opening, and the bandage material feels comfortable and smooth on the skin. The Nexcare bandage packaging has the most user-friendly labeling and maintained a strong adherence to the skin for the entire 72-hour leave-on test. The Niceful bandage package was easy to open and unwrap, felt stickiest during the adhesive touch test, could be applied with minimal difficulty, and did not hurt during immediate removal. The Welly bandage was easy to unwrap, could be applied with minimal difficulty, and maintained a strong adherence to the skin for the entire 72-hour leave-on test.

With these considerations in mind, here are our final bandage recommendations:

- Best for kids: Welly

- Pain free removal: Niceful

- Best longevity: Nexcare or Welly

- Best comfort: Band-Aid or Welly

- Most waterproof: Nexcare

- Overall favorite: Welly! The endearing designs, comfort, and longevity of wear made the Welly bandage our overall favorite.

Next time you’re at the store picking out adhesive bandages, remember these considerations to help you choose the best one for your needs.

Back to Insights + News